During the 1960s and 70s, the Emirate, flush with its oil wealth, attracted socially mobile people from all over the Arab world to build the new country. As a result of the parliamentarian system, much of the oil wealth was diverted to create a social welfare state with free education and health care for citizens; from the 1970s onward, Kuwait scored highest of all Arab countries on its Human Development Index. Kuwait was the capital of higher education, arts and culture in the Gulf. The University of Kuwait, established in 1966, attracted students from neighboring countries. Artistic life flourished in all domains: theatre, music and contemporary art. This was reflected on Kuwaiti TV, which was watched throughout the Arab world.

Kuwait freely mixed cultural influences from Baghdad, Beirut and Bombay (where many Kuwaitis had moved during the depression of the 1930s) with the nascent global media culture (Hollywood films and Japanese animations). The government was eager to develop the arts and sent artists to train abroad, while in Kuwait a complex was created with studio space for artists (Marsam Al Hur, the Free Atelier). A government committee selected thirty artists each year who received an annual stipend. The creation of the National Council for Culture, Arts and Letters in 1974 spurred further institutional development of the arts, with the establishment of museums, art magazines, etc.

The private arts sector received its impulse with the opening of the Sultan Gallery in 1969, fostering a habit of art collecting that continues until today. There are many internationally renowned art collectors in Kuwait, such as Sheikh Nasser Al Sabah, Abdullatif Hamad, Sheikha Paula Al Sabah, Farida Sultan, Amer Huneidi and Rana Sadik, to name but a few that are featured in this guide.

Kuwait became a fashionable city. Andy Warhol was invited by the Kuwaiti government in 1977 to exhibit in one of the government-sponsored venues. Yves St Laurent opened a boutique in Kuwait in the 1970s, alcohol flowed freely, and there was little censorship; as long as the Al Sabah family or Islam were not criticized, artists could get away with a lot.

These heady years came to an end in the 1980s. Perhaps the most significant event was the Souk Al Manakh stock market crash. This informal stock market, located in an air-conditioned parking that had been used to trade camels, came to be the third most capitalized stock exchange in the world before the bubble burst. It had been set up to bypass government regulation of the Kuwaiti stock market. Investors, looking for ways to invest their oil wealth, started trading in stock from other Gulf companies. There was much money to invest but little to invest it in, the private Gulf economy being still in an incipient phase. Most of the oil wealth was being managed by governments and foreign companies. This prompted the creation of ‘shell’ companies (like Gulf Medical, a failed real-estate project that was turned into a hospital and taken public) that had little or no assets to underwrite the value of its shares. But the demand for shares was so high that their price rose to crazy levels. For example, the shares of Gulf Medical rose 800% in the first months, and the company had to hire 40 Egyptian school teachers to process all the subscription forms. The higher the returns, the more people wanted to participate, creating a frenzy akin to the Dutch Tulip Mania of the 1630s. At its pinnacle, the Al Manakh stock market had 100 billion dollars in stock, based on at most a few billion dollars in real worth of assets. The crash that occurred in August 1982 was so dire that the whole Al Manakh market simply evaporated.

This event symbolized the end of the Kuwaiti dream. Although the development of Kuwait over the past decades had been truly amazing – the city had become a symbol of contemporary cosmopolitism, like Dubai today – the expectations had risen even faster. During the 1980s, falling oil prices and the bloody Iran-Iraq war that raged near Kuwait’s northern border, added to a faltering political system and a crashing economy, created disillusionment within Kuwaiti society. The government lost its focus on cultural and social development. Bahrain became the new destination for culturally open and socially mobile Arabs.

The occupation by Iraq and the first Gulf War had a major, traumatic, influence on Kuwaiti society. The anti-Iraqi, anti-pan-Arab/Palestinian and pro-ruling family narrative severed many of the ties with Kuwait’s organic past. The new Kuwait that was built on the ashes (or soot) of the old country seems to lack identity as a result: it is a ghost of what it once was.

In economic terms, Kuwait was rebuilt fast, with the assistance of the USA, Saudi Arabia and other international friends. The Palestinian and Iraqi engineers, administrators and laborers who were no longer welcome were replaced by South Asians, who generally failed to take root in the country. Until the toppling of Saddam Hussein’s regime in 2003, Kuwait lived in fear of retaliation by Iraq. In terms of artistic production, the period between 1991 and 2005 was dismally bleak.

Since 2005-2006, a fresh wind seems to be blowing through Kuwait; it may have started with the mass demonstrations by youth groups and opposition parliamentarians to counter the government’s attempts to sideline opposition in 2005. This was the year that Kuwait’s women first participated in elections, but 2005 was also the year in which the University was segregated, marking the strength of Islamism in society and politics that has been increasing ever since. The year 2006 saw the reopening of the Sultan Gallery, and several new commercial galleries, each vying for the attention of wealthy collectors and critics, have appeared on the Kuwaiti scene in its wake, or, in the case of the older galleries, they have improved their programming. Interesting artistic ventures such as JAMM consultancy, the Contemporary Art Platform Kuwait and MinRASY projects have emerged, while on the less experimental side, the Dar Al Athar Al Islamiyya is improving its program every year, and has opened a new cultural center. Kuwait is still doing well on the Arab pop music scene, while the literary scene has received a boost with the opening of the beautiful Babtayn central library for Arabic poetry. And Kuwaiti theatre has become world famous thanks to Sulayman Al Bassam and his interpretation of Shakespeare’s Richard III (An Arab Tragedy).

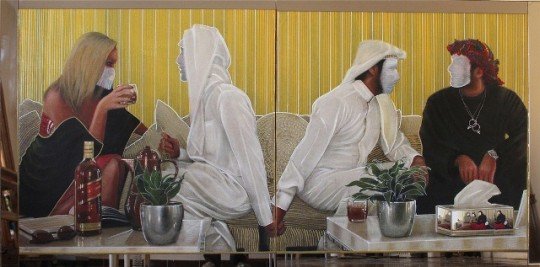

Shurooq Amin: I Like Him I Like Her. One of the artworks deemed offensive at the show closed by the police for obscenity in 2012

The worsening political crisis in Kuwait and the seemingly unstoppable progress of Islamism – witness the closing of Shurooq Amin’s exhibition for ‘pornography’ and public indecency in March 2012, or the increasingly frequent ‘gay-bashing’ by the police – make the future development of Kuwaiti culture very uncertain. Up to now, however, the arts community seems sufficiently strong to deal with these challenges in its own manner.